Part 3 of 5: Johns Hopkins Experts are Developing New Policies and Guidelines

April 24, 2018

Dome

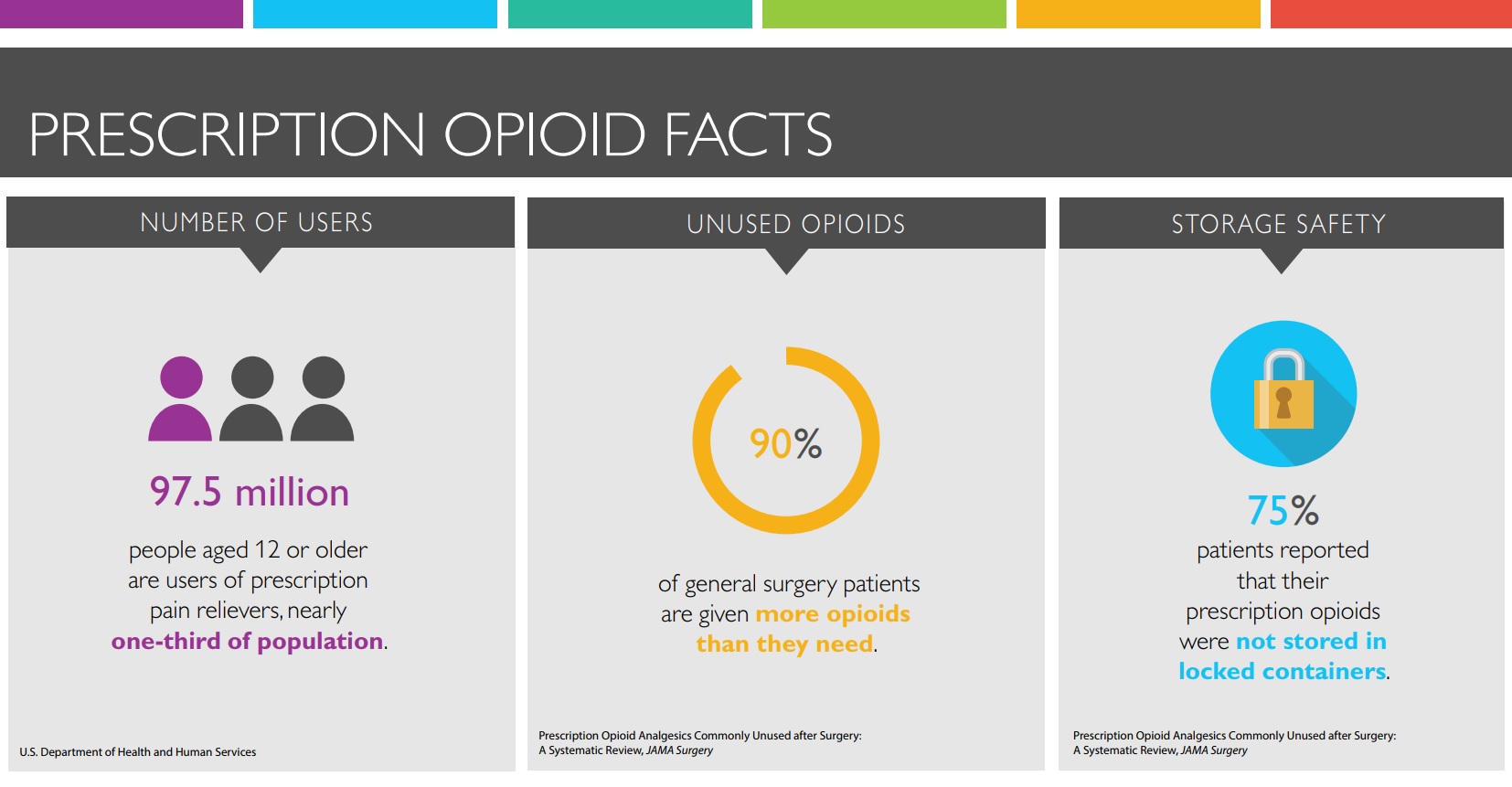

Heroin may hog the headlines, but prescription pain medication misuse affects more people.

According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 948,000 people used heroin in 2016, while 11.5 million Americans misused prescription pain relievers by taking more than prescribed or for a purpose other than their intended use.

To reduce prescription opioid misuse, the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality last year formed a clinical community of experts from throughout the Johns Hopkins Health System to take on the issue of opioid stewardship.

Mark Bicket, director of the Multidisciplinary Pain Medicine Fellowship Program

The group includes doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, counselors, administrators and patients representing all six Johns Hopkins hospitals and Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. It is chaired by Suzanne Nesbit, clinical pharmacy specialist for pain management, and Steven Levin, director of the regional pain management program. Executive champions are Peter Hill, senior vice president of medical affairs for Johns Hopkins Health System, and Dan Ashby, vice president and chief pharmacy officer.

“We decided we needed a health system approach to the use of opioids and pain management, to look at the problem holistically,” says Hill. Committees within the group have specific tasks: forming broad policies for the entire health system, developing prescribing and pain management guidelines for clinicians, tracking opioid prescribing patterns in the hospitals and working with the state and federal agencies that create opioid policies.

The clinical community is also making sure the health system stays ahead of new guidelines. For example, the Joint Commission set new pain management standards for 2018 that call for, among other things, providing nonopioid pain treatments and making sure patients have realistic expectations about their pain.

The Armstrong Institute has about two dozen clinical communities, each tackling a different problem or disease. In the case of opioids, the problem is that doctors tend to prescribe the medications before they recommend other forms of pain management: nonnarcotic pain medication and nonpharmacological techniques such as cold and heat treatment, physical therapy or exercise.

Patients are then discharged from hospitals with prescriptions for too many pills and vague advice to take as necessary, says Mark Bicket, director of the Multidisciplinary Pain Medicine Fellowship Program and co-chair, with Nesbit, of the systemwide policy group.

A recent study led by Bicket found that more than two-thirds of patients who were prescribed opioids after surgery did not use all the pills, and more than 90 percent of people with leftover pills failed to store or dispose of them properly. When excess pills are improperly stored, he says, they are “just waiting to be lost, sold, taken by error or accidentally discovered by a child.”

Residents across all departments are working to change this. The House Staff Patient Safety and Quality Council is surveying residents and fellows about why they may prescribe more opioids than necessary.

One reason, says Alexander Sun, a third-year resident who chairs the council, may be that “we want patients to have enough pills when they’re home,” so they don’t have to cope with the hassle and expense of refilling a prescription. He also notes that treatments such as physical therapy or counseling can be time-consuming for patients and aren’t always covered by insurance.

Recently, about 20 members of the clinical community’s prescribing guidelines workgroup crowded into a small room in the Sheikh Zayed Tower of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Additional members were on the phone.

The group is working to create a structure that encourages doctors to communicate with patients about pain expectations and opioid risks, to consider nonopioid forms of treatment, to identify patients at particular risk for addiction and to prescribe minimal amounts of opioids if the drugs are deemed necessary.

The guidelines workgroup is led by David Madder, an internist with Johns Hopkins Community Physicians – White Marsh, and Marie Hanna, chief of regional anesthesia and acute pain management. “As you know, we don’t have any guidelines for opioid prescribing,” Hanna told the guidelines group. “Our job is to build the guidelines.”

“The days of pulling out the prescription pad and saying, ‘Here’s a 30-day supply,’ are gone,” says Bicket. “We’ve had a fairly liberal opioid prescribing policy in the legitimate interest of relieving pain. Now we’re developing more appropriate and personalized therapies.”

Disposing of Unused Opioids

Five outpatient pharmacies at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center now have collection receptacles, also known as take-back boxes, for unused medications.

Patients and their caregivers can deposit any medication, solid or liquid, in the containers, which were installed in August. When the boxes are full, they are sent to Sharps Compliance, Inc., for incineration, says Kristopher Rusinko, assistant director of innovation and operations for the Johns Hopkins Home Care Group.

Take-back programs at pharmacies and law enforcement agencies are the best option for returning unused opioids, says the Food and Drug Administration. Next best is disposing in the trash. First, mix the medicine with an unpalatable substance such as kitty litter or dirt, then place in a sealed container. Scratch out personal information on prescription labels before throwing pill bottles away.

Glossary of Terms

Naloxone: Often referred to by the brand name Narcan, naloxone saves lives by reversing the effects of an opioid overdose.

View more opioid and pain definitions.