The Wilmer Eye Institute provides untold opportunities for those with shared and overlapping interests to pool their talents, ideas and ideals to advance science and patient care. Following are the stories of two extraordinary clinician-scientists — one, a vitreoretinal surgeon, and the other, a pediatric ophthalmologist — with a shared interest in genetic eye diseases. Together, the two co-founded the Genetic Eye Disease Center at Wilmer, a unique center dedicated to meeting the complex needs of patients with genetic eye disease.

Now they share another distinction: professorships with a common name that will help to provide vital support for their twin goals of guiding patients and families through the maze of living with genetic eye disease and working to discover new, cutting-edge therapies to treat it.

A Whole-Person Approach to Genetic Eye Disease

As co-founder of Wilmer Eye Institute’s Genetic Eye Disease (GEDi) Center, Mandeep Singh, M.D., Ph.D., sees many patients with rare, often untreatable eye conditions inscribed in their DNA. These patients have few places to turn for the comprehensive care such conditions demand. In many cases, the care he offers will extend across the span of his patients’ lives, as he provides the clinical and emotional support they need to live with the challenges of their genetic illnesses.

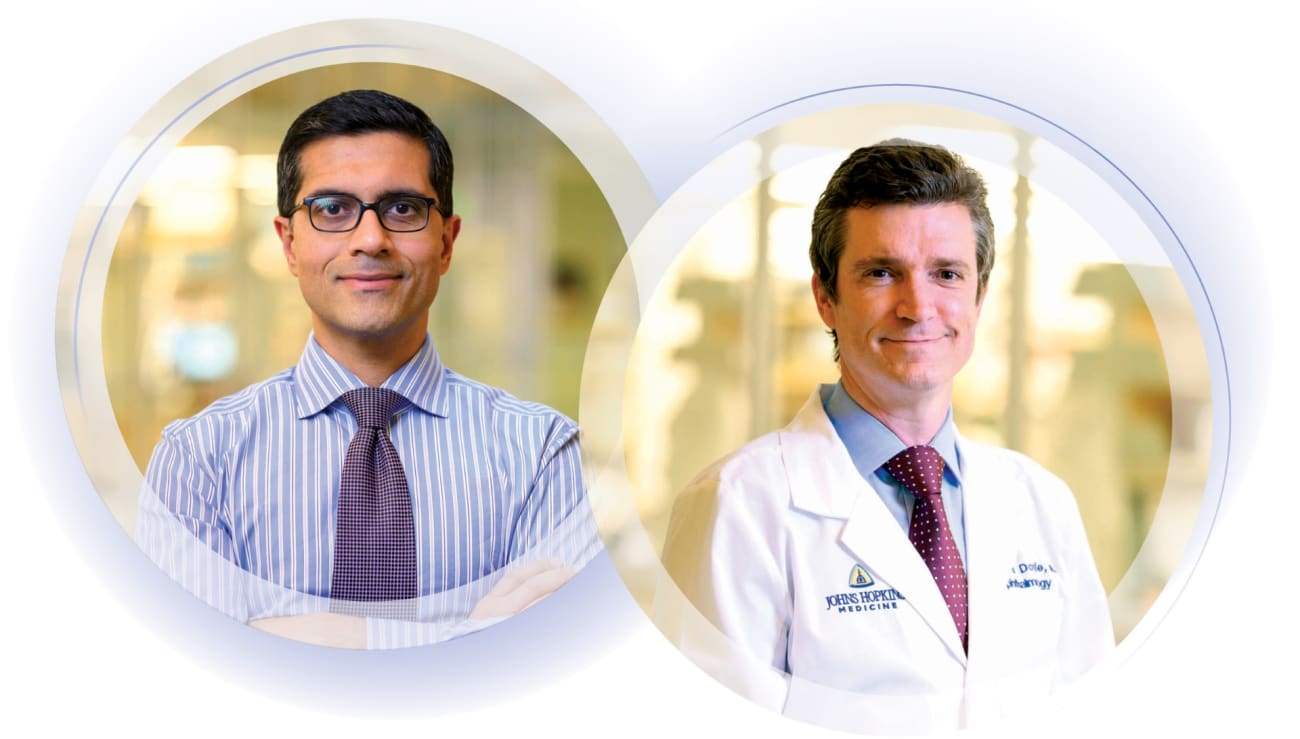

Singh, the Andreas C. Dracopoulos Professor of Ophthalmology at Wilmer, and GEDi Center co-founder Jefferson Doyle, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatric ophthalmologist with a Ph.D. in genetics, conceived of the GEDi Center as a singular place that could treat complex genetic eye diseases and coordinate care with Wilmer team members and specialists across the Johns Hopkins Health System.

“The GEDi Center centralizes ophthalmic genetics services at Wilmer encompassing clinical care, research and education of our physician peers and of medical students who will be tomorrow’s physicians,” Singh explains.

With many genetic diseases, symptoms of the eye are only the entry point to care. The diseases can and do affect other systems within the body. Patients with Marfan syndrome, for instance, caused by a mutation in the genes encoding the body’s connective tissues, often experience profound vision loss, but also damage to heart, skeletal, circulatory and other systems. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP), on the other hand, can be associated with Usher syndrome, which combines RP’s vision loss with hearing loss.

At the Wilmer Genetic Eye Disease Center, these patients find allies who understand the unique complexities of their cases. In addition to offering clinical care for each subspecialty of ophthalmology (including cornea, glaucoma, neuro- ophthalmology, pediatrics and retina), the center provides genetic counseling services as well as low vision services to assist patients’ functioning in daily life.

The GEDi Center’s services include a Wilmer first: in-house genetic testing. Prior to the center’s creation, Wilmer had to refer patients for genetic testing, a process that could take 18 months or more.

“If Wilmer is to be at the forefront of genetic disease research and clinical care, you can’t have patients waiting a year and a half to find out their diagnosis and if they’re eligible for a clinical trial,” Doyle says. “The GEDi Center has cut wait times to just three weeks.”

On the research front, one area GEDi Center researchers have focused on intently is gene discovery to reveal the mutations that cause the diseases and, more critically, to look deeper at what Doyle refers to as genetic modifiers — the second and third genes that may determine disease severity and, potentially, what therapies might work best for a given patient.

Singh notes that individualizing care is an important component of the GEDi Center mission of treating the whole patient, not just the condition — an approach and philosophy he learned from his mentor, Daniel Finkelstein, M.D. Even before he joined Wilmer in 2015, Singh knew of Finkelstein, his predecessor and the inaugural holder of the Andreas C. Dracopoulos Professorship, endowed by philanthropist Andreas Dracopoulos.

“Dr. Finkelstein’s blend of skill, knowledge and compassion were what made him such a special ophthalmologist, a special human being, and why in trying to pay tribute to his great career and legacy I endowed a professorship to support his important work,” says Andreas Dracopoulos.

Indeed, Finkelstein, who died in 2022, was an ophthalmologist of the highest order and a profoundly caring physician. Over a half-century career that began in Wilmer’s residency program in 1970, Finkelstein shaped a reputation for patient care, science and leadership. Often, he was one among a few specialists treating the rare genetic disorders behind eye diseases such as Stargardt, RP, choroideremia, retinoschisis and others. He was deeply attuned to the ethical aspects of his work. A member of the core faculty of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, Finkelstein also held an M.A. in theology from St. Mary’s Seminary.

Such was Finkelstein’s reputation that Singh reached out to him in the very first week of his appointment to the Johns Hopkins faculty. Singh remembers asking a simple question: What makes an excellent physician?

“He didn’t talk about training or technique, but about human dignity, morality and ethics,” Singh says. “We build long relationships with our patients who have chronic conditions for which there often are not cures currently. Dan Finkelstein understood how the manner of his care affected a patient’s whole life.”

Singh and Finkelstein would partner on pioneering research in stem cells and cutting-edge gene therapies, including laboratory research and clinical trials. Singh says Finkelstein’s focus on ethics and morality has touched every patient.

“I’m extremely interested in the bioethics of recruiting patients into trials,” Singh says. “We need to think about their vulnerability. We owe them an honest appraisal of their prospects while reinforcing their critical role in advancing knowledge with the potential to improve treatments, possibly for themselves, yes, but more significantly for other patients in the future.”

As Finkelstein eased into retirement, Singh took on the care of many of his long-term patients. In 2023, a year after his mentor’s death, Singh stepped into Finkelstein’s shoes as the Andreas C. Dracopoulos Professor of Ophthalmology.

“Dr. Singh is an ideal physician to pick up the mantle of Dr. Finkelstein’s work and to carry it into the future,” says Dracopoulos.

Finkelstein’s philosophy continues to influence the GEDi Center’s patient- centered approach. “Every time I walk into my clinic, I think of Dan Finkelstein and the honor and dignity he brought to so many,” Singh says of the legacy he now inherits. “It is among my greatest fortunes to have met and learned from him.”

Life Through a Different Lens

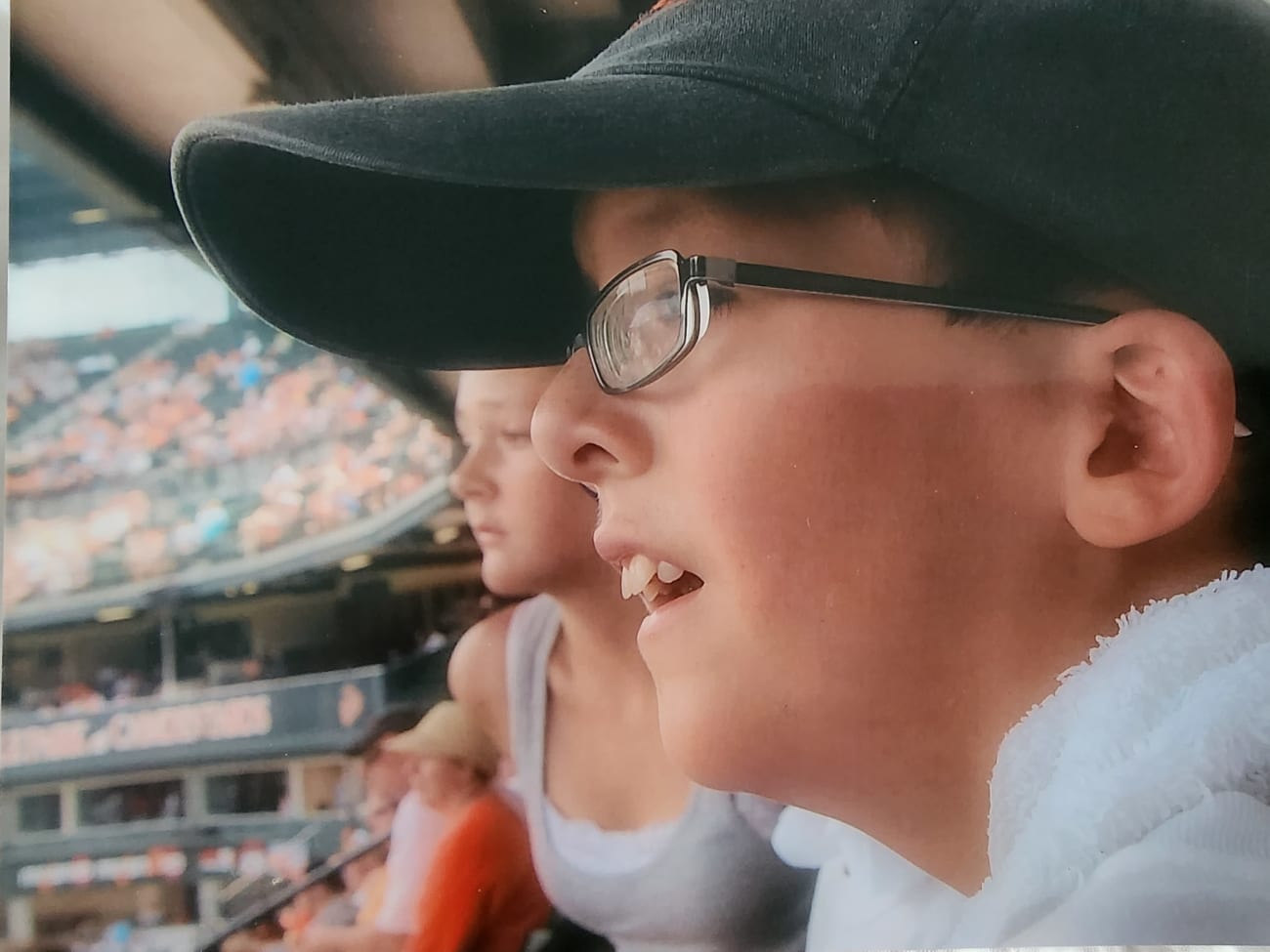

Caden Crawford is not unlike many 20-year-olds. He likes video gaming and computers, and he recently earned a college degree in computer science. Caden also has Marfan syndrome, which is caused by a mutation in one of the genes that encode a protein critical to the connective tissues in his body. Today, patients with Marfan syndrome usually live normal lifespans because of advances in aortic surgery. But the symptoms are chronic and often widespread. Caden feels the effects of Marfan in his heart, in his bones and, quite acutely, in his eyes.

“I realized how bad my eyesight was getting when I was in high school. I’d get stronger glasses and move to the front of the class, and I couldn’t even read the board most of the time,” Caden says of the severely declining eyesight that brought him and his mother to the Wilmer Eye Institute.

“Genetic diseases, like Marfan syndrome, require a remarkable breadth of care that can’t easily be found in one place,” says Jefferson Doyle, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatric ophthalmologist, surgeon and co-founder, with Mandeep Singh, M.D., Ph.D., of Wilmer’s Genetic Eye Disease (GEDi) Center. “Many patients spend years going from doctor to doctor, hospital to hospital, seeking out specialists for each affected system.”

In his young life, Caden had already endured spinal surgery and a heart valve replacement. The longstanding problems with his eyes included a severe ectopia lentis — lens displacement — reducing his vision to the point that his eyesight fell in the highly myopic range even with the strong glasses he was never without. He was even known to wear his glasses to bed.

“Caden’s care was always sort of a balancing act with a lot of different doctors,” says his mother, Christy Crawford. “We couldn’t find one group of doctors who did it all the way Wilmer and Johns Hopkins could. We now see several specialists at Hopkins all coordinated through the Wilmer GEDi Center and Dr. Doyle.”

Like Caden, many of the GEDi Center’s patients have symptoms from birth, and their diseases often have no cure — at least not yet. They will require a lifetime of care.

“In that respect, Dr. Singh and I complement one another, as we cover both pediatric and adult ophthalmic care,” Doyle says of the partnership that has proved so fruitful in delivering the whole-patient, long-term care GEDi is known for. “Mandeep cares for parents and grandparents. I see the kids.”

Doyle’s expertise was recently recognized when he was named the recipient of the Andreas C. Dracopoulos and Daniel Finkelstein M.D. Rising Professorship in Ophthalmology. Such rising professorships, launched at Wilmer in 2021, provide seven years of funding for early-career physician-scientists who show exceptional promise.

The professorship was endowed by philanthropist Andreas Dracopoulos to honor longtime ophthalmologist, the late Daniel Finkelstein, M.D., a beloved leader at Wilmer for 50 years. Finkelstein was known for caring for patients with the rarest cases with equal parts compassion and resolve.

“This singular ability to treat patients with complex and rare genetic conditions is what sets Wilmer apart. But finding specialists with the training and patient-facing skills to treat the whole person is almost as rare,” Dracopoulos said of his motivation for supporting the rising professorship. “When you see someone like Dr. Doyle, with that key combination of skill, promise and manner at such a relatively young age, you want to make sure they get the early-career support they need to accelerate their careers.”

In GEDi and Doyle, the Crawfords found a single center and a single doctor able to coordinate the care of Caden’s eyes, heart and bones within the Johns Hopkins medical family. GEDi’s one- stop proposition proved so compelling to Caden’s mom that the four-times-yearly, 18-hour roundtrip drives from Indiana were more than worth it.

“Baltimore became a second home. We would just make a small vacation out of the trips east,” Christy recalls. “I don’t know what we would have done without GEDi.”

What impressed the Crawfords most was Doyle’s caution. Rather than rush to surgery, Doyle stepped back and analyzed Caden’s many complicating factors. Doyle diagnosed Caden with significant dislocations of both lenses, early-onset cataracts and heightened surgical risk to his retinas. Caden’s history of spine and heart surgeries required that he be on a blood thinner, but that increased the risk of intraoperative and postoperative bleeding with his eye surgeries.

Doyle recalls much concern over Caden’s anticoagulant regimen and the potential effects of anesthesia. Eventually, however, it was clear that the need for surgery outweighed the risks. In the summer of 2021, Doyle and Singh jointly performed sequential vitrectomies, lensectomies and the implantation of new synthetic lenses — first one eye, then when it was clear that surgery was a success, the second followed a month later. Eighteen months post operation, Caden now enjoys 20/30 vision in both eyes.

“He doesn’t even wear glasses,” Christy says. “It’s been a complete turnaround.”