Inside Tract

July 15, 2013

Those less-than-ideal options prodded gastrointestinal motility specialist John Clarke and colleagues to a new approach: Rather than cut the pyloric valve, why not insert a stent to bridge the stomach and small intestine?

Now, results from three stent placements are promising. The write-up is soon to be published in the journal Endoscopy.

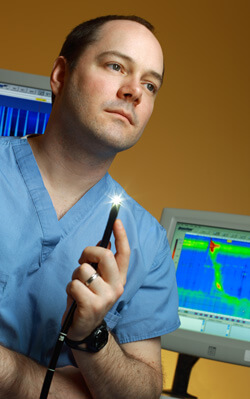

“I think this technique could potentially play a big role in the treatment of gastroparesis,” says Clarke, clinical director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Neurogastroenterology.

All of the patients that Clarke describes showed dramatic reductions in symptoms. A 15-year-old boy with chronic nausea and vomiting, for example, had endured unsuccessful trials of erythromycin, metoclopramide, domperidone and promethazine. He showed significant improvement after undergoing transpyloric stent placement. A 54-year-old man with idiopathic gastroparesis who also didn’t respond to medication experienced a complete recovery.

A third patient had minor complications that were remedied with relative ease. “Her stent migrated out and her pain came back,” says Clarke. Things were once again fine after the team repositioned the stent.

Technically, stent placement is pretty simple, says Clarke, and the risk appears to be minimal. “If it doesn’t work, you just take it out,” he says. “And, as opposed to gastric stimulation, which is done through surgery, this is just endoscopy. Although this sounds a bit unconventional, its safety looks better than anything else we have.”

Clarke explains that advances in stent technology played a key role in his team’s decision to move ahead with the pyloric stents.

Recently, the field’s seen creation of a flexible, covered stent “that you can place via the endoscope,” Clarke says. “The stent is metallic, but covered with a silicone lining so that the mucosa won’t grow into it. The stent was approved to treat obstructions, but hadn’t yet been used to treat gastroparesis.”

The number of patients with a gastroparesis diagnosis is on the rise, Clarke says. “I’d estimate that 30 percent of my clinical practice comprises patients with gastroparesis. And only about 30 percent of them are diabetic. Most of the patients I see have idiopathic disease.”

In the next few months Clarke expects to begin a larger trial of the stent placement.

“This is an experimental therapy, and the long-term benefits are unclear,” he explains. “However, given the few options currently available and the risk associated with those options, endoscopic stent placement may have a key role to play in managing this complex disorder.”