Inside Tract

Inside Tract

November 28, 2014

Even though the human body needs the right amount of copper for red blood cell production, various metabolic processes, bone health and healthy connective tissue, it’s also important, of course, that bodies can clear that copper.

Wilson’s disease is a rare genetic disorder that causes copper buildup in vital organs, especially the liver and the brain. Hepatologist James Hamilton specializes in the disease and is researching new ways to treat it.

“People with Wilson’s disease all tend to have too much copper. But for some reason, some people get sick from it, and some don’t. And it can be 18 or even 24 months before a true diagnosis is made. By that time, a lot of damage can be done.”

The symptoms and effects of Wilson’s disease vary widely, making it sometimes difficult to diagnose. “In the brain, we’ve seen it cause neurological, as well as emotional or behavorial problems,” Hamilton says. “With liver symptoms, you can have twins who have the same mutation, and one has cirrhosis, and the other doesn’t even have hepatitis.”

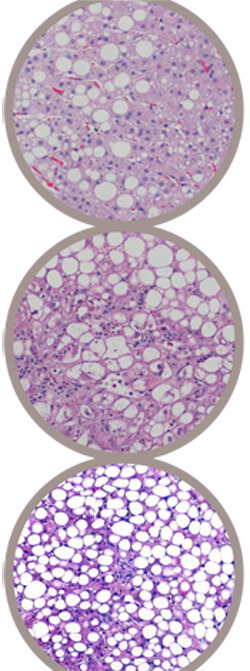

Wilson’s disease can cause a wide variety of liver problems, ranging from mild, chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis and even acute liver failure. Interestingly, in addition to elevated hepatic copper levels, it is very common to find large amounts of fat in the liver. In fact, the striking similarity to alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease presents one more barrier to a quick diagnosis.

Hamilton sees a panel of adult Wilson’s disease patients and works with a team of researchers devoted to learning more about the disease and its treatment.

Instead of focusing solely on ridding the liver of copper, they’re working on a project that aims to change the way the liver responds to copper.

Their work points to promise in the area of liver X receptors, which regulate cholesterol, fatty acid and glucose homeostasis. They introduced a drug that activates liver X receptors to mice with copper-related liver disease. Without changing the mice’s copper levels, the research team “basically cured these mice’s liver disease,” Hamilton says. “The copper is all still there, as high as 38 times the normal levels. But the liver is better.”

Hamilton and the research team are still working on the liver X receptor project and have hopes it could lead to a treatment breakthrough.

“Doing things in mice is very far off from doing them in humans. But we’re taking a totally different approach to treating this disease without affecting copper.”

The work has implications for both the brain and liver problems caused by Wilson’s disease. “If we could change copper’s ability to cause problems, it would be pretty exciting.”